THE SAINT PAUL TOY BULLDOG… THE RISE, FALL, AND UNTIMELY DEATH OF JIMMY COLLINS

BY JAKE WEGNER. There is an old saying that everyone is familiar with, “The bigger they are, the harder they fall”. It was almost as if it were written on the life and career of Saint Paul’s colorful Jimmy Collins, whose hot career began at barely Welterweight, then Middleweight, and rapidly straight to Heavyweight. And the heavier he got, the harder he fell, although not in the ring. For Jimmy’s 56 professional fights paled in comparison to his record in the streets, in the alleys, inside a café, with Ft. Snelling Army soldiers, with police officers, with innocent bystanders, and all of the other many places outside of a prize ring that the Irishman’s temper-filled fists went into action. His early departure from this earth at the age of 44 was both sad, and well-documented. Let’s light up his name one last time. Let’s take a look at the life and career of the man they tagged, “The Saint Paul Toy Bulldog”.

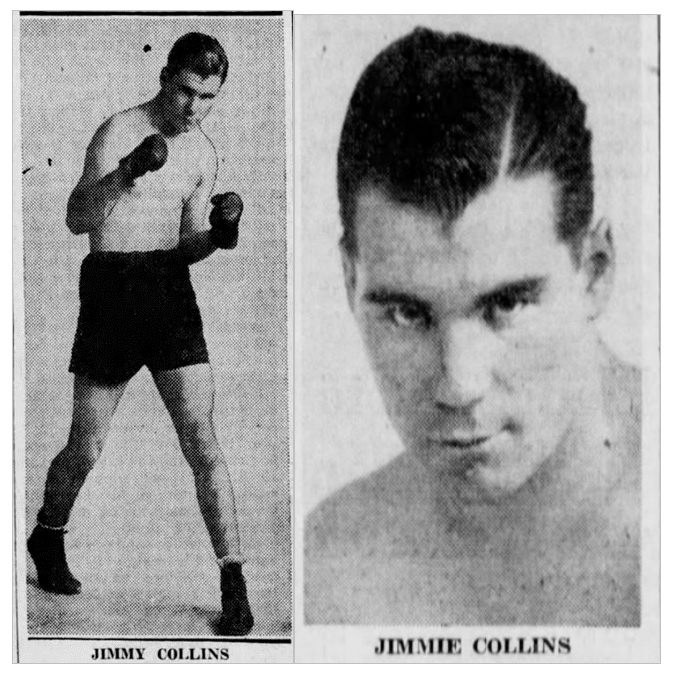

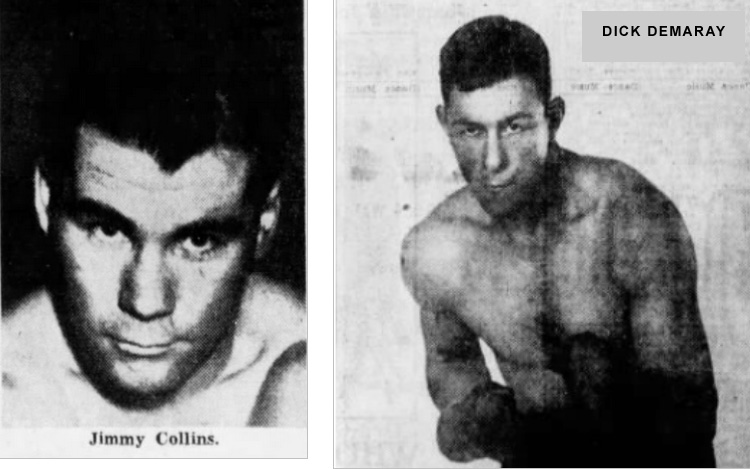

The life of Jimmy Collins began on August 13, 1918 in Iowa. When Jimmy was young, the family moved to SE Minneapolis, present-day St. Louis Park. He was a natural athlete and attended the former West High School; the same high school that produced actress Tippi Hedren (The Birds) and businessman, Curt Carlson (founder of Carlson and Radisson Hotels). He began boxing in 1933 at the famous Potts Gymnasium and competed in the amateur ranks, coached and trained by the great Jimmie Potts himself, as well as Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame trainer, the one and only, Leo Ryan. It was Potts who first noticed both the natural athleticism and fighting instincts in the young, and extremely cocky Irishman, and instructed Leo to pay special attention to him. Ryan did, and Collins was tagged by the newspapers as a “natural born fighter” almost from his first outing in the simon-pures. In fact, it wasn’t long before young Jimmy was stealing the usual spotlight from the bigger amateur names who were supposed to be the main eventer’s; men such as Verne Trickle, Earl Sather, Frank Androff, and Russ Wasser (Russ Schultz). His cleverness inside a ring was one thing, but his natural instincts, (i.e. moves and counter-punches that took others countless hours in the gym to master) ability to take it as well as give it, and flat-out zeal for blood in the punch game are the most common words and phrases writers used when watching Jimmy Collins fight.

Throughout 1933 and early 1934, Jimmy was making regular headlines for his victories over stiff amateur competition and was being labeled as a leading contender for the Golden Gloves Welterweight championship until he broke his right hand in his victory over Ad McNeil of the Pillsbury House Gym in the first round of the tournament, thus ending his title aspirations. The pre-eminent referee and fight reporter, George Barton, began calling Collins, “The King Tut of the amateurs”, after his aggressive style and incredibly skilled ability to score with remarkably short punches, which greatly resembled professional Welterweight, King Tut’s. It was quite a compliment and from a man who knew boxing better than any in his time. It was time to turn pro, and Jimmy did, signing on with businessman A. V. Satterstrom as his manager.

How Collins was able to turn pro at the tender age of 16, is uncertain, although like many young aspiring boxers, he most likely lied about his date of birth. But many state boxing commissions during the Great Depression were noted during this particular time in history for turning a blind eye to age when it came to licensing, as they were all-too aware of the financial struggles that every family was saddled with. So on November 5, 1934, a barely 16 year-old prospect began his fight-for-pay career at the Minneapolis Auditorium as one of the curtain-raisers of the Britt Gorman – Johnny Gaudes card. He would steal the show. Everyone loves watching aggressive fighters in the ring, and especially one with some skill to go with his brawn, and that was Jimmy Collins all the way. He had his opponent, Oliver Andrews, on the canvas 8 times before referee Johnny Sokol stopped the carnage. George Barton commented, writing the below piece in his 11-8-34 Star Tribune column:

The headlines in 3 different papers were nice for Jimmy, but he didn’t need them to develop his ego. He already had that. You see, Jimmy Collins’ natural abilities and boxer-puncher style had yielded him much success in a very short time in his brief amateur career, and that fueled an already ambitious and high-strung Jimmy to believe he could beat anybody they put in front of him and at any time. Although not at all a bad belief system to possess for a fighter, it can be a toxic load when that fighter also loves the nightlife as much as he loves the ring, and Jimmie Potts had concerns about this for Collins even before he turned professional, as rumors of Jimmy being intoxicated and using his hands in the street had already found its way back to the Potts Gym. He was indeed, a hot prospect with loads of talent and a penchant for rapid learning, but one with a love for the fast life and the bottle, and he abhorred training with a passion on a level not seen since My Sullivan was escaping training camps for moonlight moonshine. Collins also had a famous temper, and it could appear on a moment’s notice and without warning, and it often did inside Potts Gym during workouts with Bud Glover and Henry Schaft.

Long-time ring veteran, Bud Glover, had been fighting professional since 1928, and had over 40 pro fights under his belt to Jimmy’s single fight ledger. He resented Collins’ cocky attitude and swagger at Potts’, and told many people so. This got back to young Jimmy and the two agreed to “spar”. Neither Leo Ryan nor Jimmie Potts even realized what was happening until a crowd formed around the ring and plenty of blood was all over each boxer, and there was little in the way of rules being adhered to in this “sparring session” as the two tore into one another…24 year-old man and ring veteran, against 16 year-old hotshot, just a single fight into his professional career. The two were torn apart and Glover called Collins nothing but a “cocky, young, upstart, who should be put in his place as soon as possible.” Collins maintained that he could take his more experienced rival at any time. Former boxer, now matchmaker, Mark Moore; heard of a possible “natural” in the making and signed both to settle their differences in the ring. The fight took place on November 15, 1934 and Collins gave a savage beating to his gym rival and took the decision easily.

Collins finished 1934 at 5-0-1. 1935 started off seeing Jimmy have 3 consecutive draws, but one was especially noteworthy, and that was the fight with Proctor sensation, Wen Lambert. Lambert was a hot prospect himself, and carried more experience than Jimmy, sporting an 11-1-1 record. The fight was a torrid affair and when Collins achieved an even showing, writers took notice. A week later he took on and whipped Winona’s 19-9-2 Herbie Schultz. He quickly rattled off two more victories before losing a newspaper verdict in Iowa to hometown favorite, Jack Harding, a decision even the Iowa papers struggled with, calling it a “hairline margin”.

In September of 35’, Collins signed to fight former amateur star, and future Minnesota Lightweight champion, Emmett Weller in a 6 rounder on the undercard of the highly anticipated state Heavyweight title fight between Charley Retzlaff and Art Lasky. It was a fast-paced and viscous battle where each man had his moments. Collins almost had a knockout in the 2nd round when he had Weller badly hurt and wobbly, but Weller survived and came back to win the next two rounds, though Collins staged his own comeback and won the final two stanzas, and with it, the decision. The Weller fight would be his last of 1935, as he finished the year at 9-1-4 and with a growing reputation for always stealing the show, despite fighting on undercards.

The Irishman opened 1936 a bit rusty after a five month layoff and a series of proposed bouts that never came off, and he dropped a decision in Eau Claire to the tough, but beatable, Ralph Leslie over 6 rounds, despite dropping Leslie for an 8 count. Jimmy then began letting his taste for booze and Irish temper get the best of him, as he began getting arrested on a regular basis for bar fights and public intoxication. These altercations, plus a fractured right hand, all contributed to a year that hardly existed for Collins, as he fought just the one time against Leslie. He was scheduled to fight in St. Cloud in the summer but that fight fell through when his opponent backed out. He was also scheduled to fight on Duluth promoter, Red Hanson’s card on September 11th, but failed to show up, prompting a suspension by the state commission, but was later reinstated just before Christmas. 1937 was another year of little activity for Collins, as he went 3-2-1 to finish the year, although both of his losses were in fights he was dominating until his temper got the best of him, and he committed serious fouls, costing him those matches.

The Phantom Gets Involved

Mike Gibbons had watched Collins fight on many cards and in December of 37’, he began working with Collins, whose aggressive style he believed resembled that of the great Mickey Walker, and columnists began calling Collins, “The Saint Paul Toy Bulldog”. Collins claimed the tips and techniques learned from Gibbons helped immediately, and it was obvious, as he kayoed Johnny Dobbins after just one training session with Gibbons to finish off the 1937 season. 1938 would be even better, as Collins went 12-0-2 fighting across Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Chicago and finishing the year at 24-4-6.

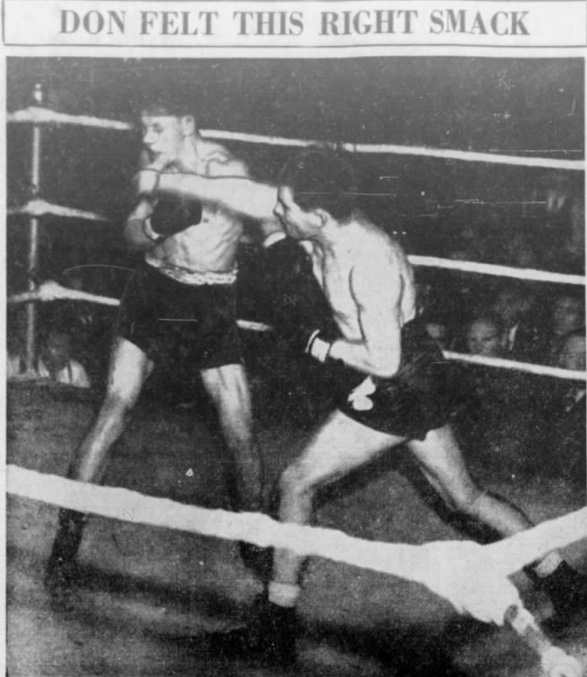

In late 1938, Jimmy Potts began hosting weekly cards at the Palace Theater and folks had been clamoring for a bought between Collins and fellow Minneapolis prospect, Don Espensen. Espensen had the reach of a Heavyweight, although not the punch, but had crazy boxing skills. The two signed to be the main event on January 16th. Collins beat the hell out of Espensen over their 6 round main event and made it look easy, though Espensen later begged for a rematch, claiming he had discovered weaknesses late in the fight in Collins. Collins granted it and the bout was set for late March and the fight was scheduled to be refereed by former world champion Lightweight, Benny Leonard. But before they were to have their rematch, Collins signed for a $1,000 (about $19,000 in 2021) to face South Dakota killer southpaw, Dick Demaray. There were two fighters from South Dakota that always seemed to be unbeatable when fighting in a Minnesota prize ring, Solly Stark, and Dick Demaray; and both fought here so much, they could have easily called Minnesota, home base.

The fight was scheduled for late March, but had to be postponed after Jimmy was arrested for fighting rival, Henry Schaft in an alley and was subsequently arrested. But first he had to deal with the pesky Espensen one more time over an 8 round main event. Espensen was in shape and ready, and Collins was flabby and out of shape for the bout, having hardly shown his face around the gym anywhere near as much as he was showing it around the bars. Jimmy entered the ring at 153 lbs. to Espensen’s 149, but he looked much heavier than that. It was an unspectacular affair, and referee Benny Leonard declared it a Draw. The crowd disagreed and so did the local papers, as The Minneapolis Star had it 39-33 in favor of Collins. But Leonard did feel that Collins could have won had he been in shape, and was overheard after the fight asking one of the ringsiders, “Isn’t it a shame that kid doesn’t get himself in shape?” Collins overheard the comment and was said to be hurt by it, and Jimmy would come in almost 10 pounds lighter for the big Dick Demaray showdown.

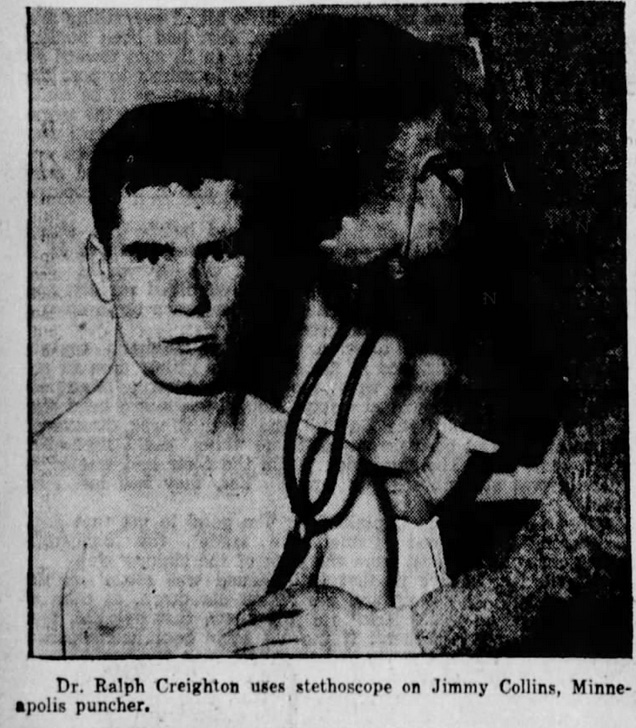

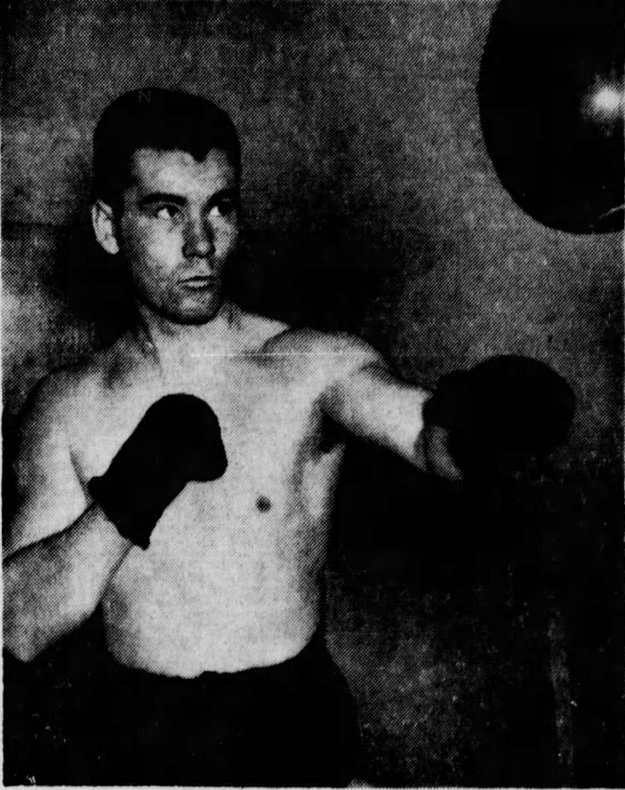

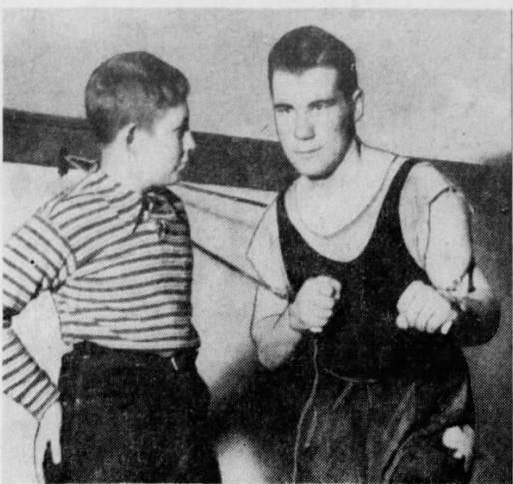

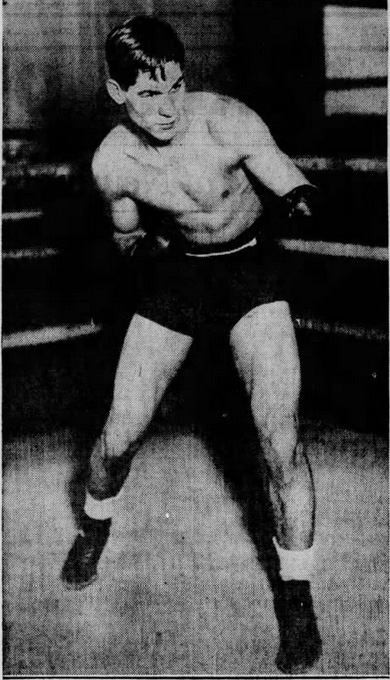

Collins hitting the speed bag at Potts Gym preparing for Dick Demaray

Collins’ weight had been increasingly climbing, as he no longer resembled the the 140 lb. amateur prospect catching headlines. He was a full-fledged Middleweight, and had been for several fights now, and although his weight was mentioned in the papers quite a bit, his skills under Mike Gibbons seemed to be improving, although after his arrest for street-fighting, Gibbons left him, and without the discipline and savvy advice from Gibbons, there was no one left to babysit young Collins, and his career began to slide as his weight began to climb. No longer could Collins get by on athleticism and boxing instincts while fighting much bigger men, yet for Demaray, he made a return to his natural weight class of Welterweight, coming in at 146.5 lbs. Had he been able to train diligently and consistently, he easily could have won the state Welterweight title from Tony Yates, who was talented indeed, but would have been no match for Collins according to the fight experts of the day.

Collins trimmed weight quickly for the fight, even giving up booze and everyone was saying he was in the best shape of his career. He told the papers if he beats Demaray, he will proclaim himself the Welterweight champion of the Northwest. Demaray was training at his farm until two weeks prior to the fight when he arrived in Minneapolis for sparring and impressed all with his sessions against future state Light Heavyweight champion, Kelly “Butcher Boy” Ward.

Many fight writers had the fight at dead-even odds, but not Charley Johnson of the Minneapolis Star, as his heart had been broken too many times by the young Irishman and wrote the below column a few days before the brawl at the Armory.

A day before the bout, Collins asked the state commission for two judges to score the fight in addition to the referee, which had been done before in Minnesota, although Minnesota had only allowed decisions solely made by the referee for years. Collins’ camp was not the only one with requests. Demaray’s manager, Isham Hall, believed referee Johnny DeOtis to be biased against his stable of fighters and demanded a different referee such as Britt Gorman. In the end, the commission ruled DeOtis would stay and be the sole judge.

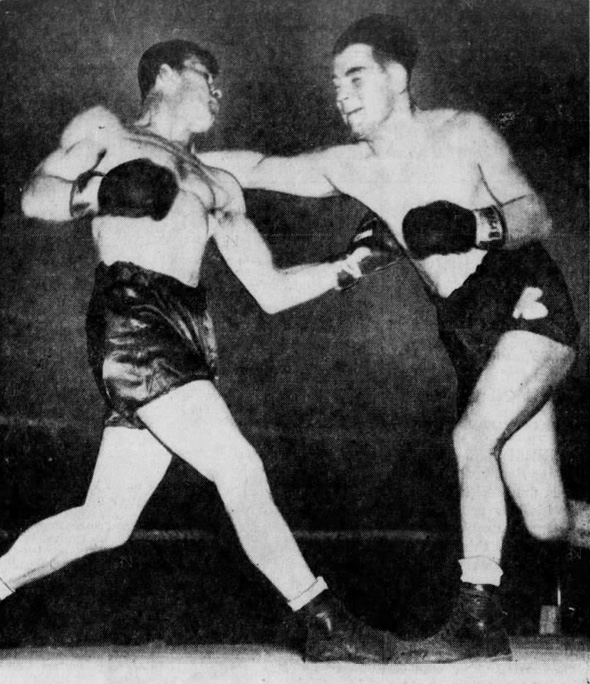

Although Jimmy fought gamely and even cut Demaray’s eye in the second round, it would go down in state history as one of the most brutal beatings ever administered on a Minnesota boxer, as Demaray was far too experienced and clever for the young Collins, winning every single round, and dropping Collins in the opening stanza. He made Collins miss far more than he landed, and then countered with furious two-fisted attacks. In the 9th round, Collins was badly busted up and battered around the eyes, mouth, and had some major welts around his body. A fantastic right to the gut from Demaray folded Jimmy over and then the southpaw landed a terrific left hook to the jaw that writers said DeOtis could have counted to 50 and Collins would have still laid there flat as a pancake. It was Jimmy’s shot at the big-time, as a win over Demaray, who was reported to have had over 200 fights (boxrec shows a total of 161), would have meant future offers for big money around the country. But it was not to be. Collins took almost three months to heal before being able to train again.

After the defeat to Demaray, Collins’ friends said he began to care less and less about boxing, and more and more about the playboy life; the exact thing he needed so badly to stay away from. His training dropped off considerably, and his weight began to climb even more. He began looking at the fight game only as a means to support himself and his lifestyle. He was now 26-4-8 but essentially, he was mostly through as a professional fighter.

In July of 39’, he stole gasoline and then got into a bar fight a little while later before the law located him. He had knocked a man unconscious in the bar who had gotten into an argument with him. Unfortunately, trouble of this sort was now so normal for Jimmy, that he’d be a rich man if paid for his outside of the ring battles as well as his inside ones. To make matters worse, Collins resisted arrest and even tried to punch one of the arresting officers. The once very promising prizefighter was sliding faster and faster toward the abyss and no one seemed to care… not even Jimmy.

Despite his troubles, he remained a very popular, crowd-pleasing, blood and guts fighter that fans loved to watch. His fight with Gordon Wallace, former Welterweight champion of Canada, was the semi-windup for an outdoor card at Lexington Park in August and was one fans looked forward to more than the main event of Arne Andersson and Ed Murray. Jimmy showed up to fight and showed very well until the 4th when Wallace began to take control and never looked back, winning the decision. But Collins was a hard one to figure out. Training? Not too much. Love for fighting? You bet. It began to be tricky to predict which Jimmy Collins would show up for bouts, but the old Jimmy showed himself against Earl Peterson and whipped him thoroughly and then did the same to Jerry Hayes before facing Demaray’s buddy, Solly Stark in November. Jimmy came in at a career high of 161 and looked pudgy. It would still be the fight of the night, as Collins took the first two rounds before the Deadwood Middleweight came back with his own assault and the fans all said it resembled a bar fight and would love to see it again over 8 or 10 rounds.

After the close loss to Stark, he beat Earl Peterson once again before dropping a decision in California to Lloyd Delucchi and another to Johnny Marquez in Montana over 10 hard rounds. Jimmy fought next in June of 1940 and now was a Light-Heavyweight, coming in at 174 but beating Otto Buettler over a 5 round affair, a fight he took on short notice and a healthy diet of beer and alley sparring sessions. He was then out of commission for months trying to heal a broken right hand before facing Billy Gillespie, a promising Heavyweight prospect. Collins had no business fighting a man as big as Gillespie, but there he was, fat and out of shape. But he did well. He had Gillespie on the floor 3 times before a clash of heads caused a huge gash in his lip requiring 3 stiches and referee Bud Hannigan to stop the fight. Collins demanded a rematch. He’d get it, but not before beating St. Paul Heavyweight prospect Johnny Stevens, a shocker to many considering Jimmy was a natural Welterweight now fighting far out of his weight class.

The Gillespie rematch would take place in January of 1941 at the Minneapolis Armory. It was on the undercard of Dick Demaray vs. Emmett Weller, a fight in which Demaray would continue his dominance over Minnesota boxers, knocking Weller to the mat 10 times in the affair. For all the action of the first encounter between Jimmy and Billy, the rematch was a dud. Jimmy was too fat at 181 pounds to do much, and Gillespie fought like he was afraid to engage, but did barley enough to win a decision. Jimmy then lost a close verdict to rising Minneapolis prospect, Gordie Palmer over 6 rounds and then took 10 months off to get into more bar fights and drunken arrests (fighting 3 men at one time) before losing another to future Minnesota Heavyweight champion, 205 pound Paul Hartnek in Minneapolis over 6 rounds. Collins was 185 lbs. Again, the papers commented on what a Welterweight, or at best, Middleweight, was doing fighting at Heavyweight. The grossly overweight Irishman whose belly was reported to be flopping around over his trunks, asked for a rematch and got one, this time impressing all with a hard fought Draw verdict over the future champion, and much larger fighter in Hartnek.

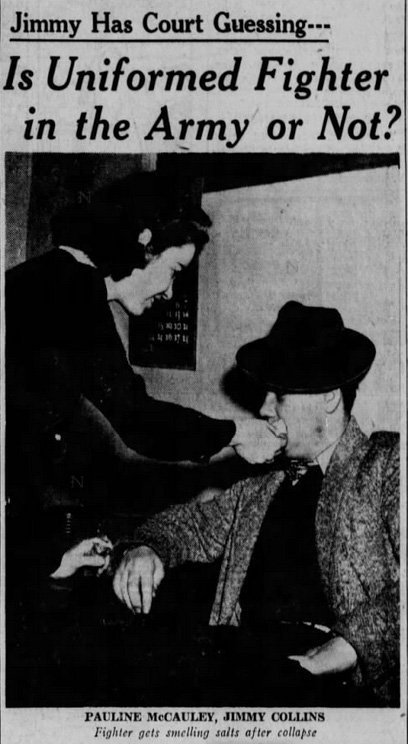

In January of 42’, he faced Ted Morrison from St. Paul; a man he had thoroughly beaten a year earlier, this time losing badly in a winner-take-all money affair for $60 (about $970 in 2021). It was the only way the promoter could afford to add the Irishman to the card, so Jimmy walked away with a bruised ego having been knocked through the ropes in the final round and losing his style of alley-war fight to Morrison…and no money in his pocket to show for it. Collins should have walked away a few years ago before he began fighting Light-heavies and Heavies. He should have walked away after this fight, but he didn’t. He needed beer money. Yet, he still kept on getting arrested for his two weaknesses…drunkenness and bar fighting. While in court facing charges, he faked fainting, and pleaded with the judge to let him go as he was enlisting in the Army, even going so far as to wear an official Army uniform to court. The court later inquired to the U.S. Army and found that Jimmy had never enlisted. He had, however, joined the National Guard, but failed to attend drills, which he claimed was the result of injuries sustained from an automobile accident. You can’t make up this sort of drama.

He took one more bout with one of Iowa’s all-time greatest fighters in Andy Miller in April of 42’ in Sioux City, and lost a newspaper decision over 8 rounds, as Iowa still did not allow official decisions yet. I guess it’s only fitting that he would have weighed a career high of 190 for the last fight of his career, but sure as lucky Irishmen are, Jimmy came to fight and knocked down the Iowa legend in the opening round with one of his famous short-range right hands. But Miller rebounded and gained enough points to wins the verdict in eyes of both newspapers covering the fight. His career was over with a record of 32-15-9.

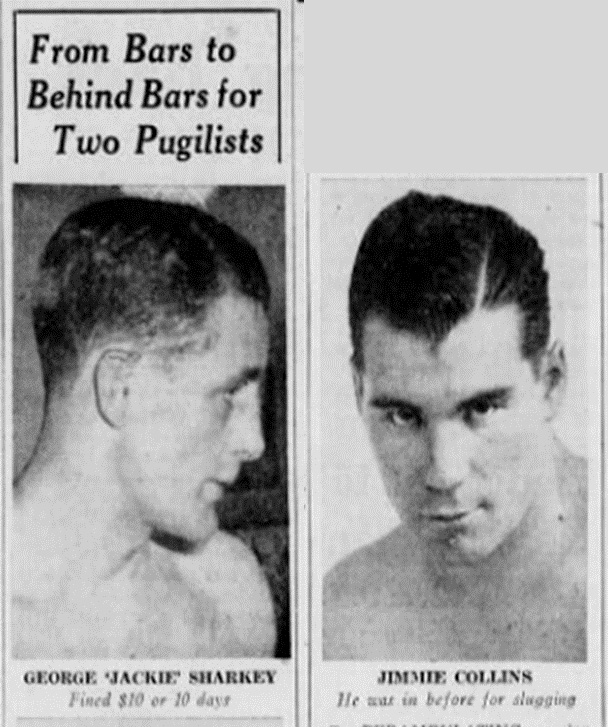

After the loss to Miller, Collins just began to fade away, both in life and in boxing. Divorce (who could blame her?), and countless more arrests. Folks knew where to find him, but few dared to seek him out at his favorite taverns, never knowing how the alcoholic former prizefighter would respond or react, even to nice greetings. It wasn’t long after the Miller fight that Jimmy and his best friend and former boxer, Jackie Sharkey, cleaned out a bar showing those imbibing that they still had their fistic skills.

Not long after this, Collins picked the wrong opponents at a St. Paul saloon when he tried fighting not one, but two Ft. Snelling soldiers. He was banged up and jailed.

The Grudge Fight That Never Was…

Grudge fights have always sold well…if they take place. It’s always a tragedy for fans when they don’t. Collins’ bad blood with fellow banger, Henry Schaft, was one of the all-time fights in Minnesota history that needed to take place, but never did; at least not in a prize ring. The two hated one another stemming from a heated sparring session and always seemed to end up at the same night spots. They fought in alley street fights, a whopping total of 11 times. 11 times. Every one of them landed Collins in the clink, and Schaft was jailed on 6 of those. This prompted Minneapolis cops to be overheard joking about who would win in their proposed boxing fight while also joking and asking the question, “Do the 5 extra arrests from their street fights mean Collins is tougher than Schaft, or that Schaft is in better condition on the theory that he outran the cops on 5 more occasions than Collins did?” Unfortunately, the fight although signed for twice, never materialized in the ring, and the long anticipated, widely talked about match between Schaft and Collins, never took place, and remains one of the all-time tragedies in Minnesota boxing history.

Henry Schaft In July of 44’ a hungover Collins didn’t like the service he was getting while eating breakfast at a St. Paul café, so he picked up a ketchup bottle and struck the owner in the face, loosening a handful of teeth. He was arrested for assault and served 90 days in the workhouse.

On July 17, 1948, Jimmy attempted to rob John Broines in downtown Minneapolis. Broines objected and was knocked down by Collins. Jimmy was arrested and jailed.

A few days later he was arrested for drunkenness and fighting and sentenced to 90 days in the workhouse.

Headlines of various arrests became very common throughout the 1950’s, and short articles might appear on how sad it is to have seen the waste of talent of former boxer Jimmy Collins.

In 1951 Jimmy was arrested on multiple counts of disorderly conduct and two counts of petty larceny for cashing worthless checks. It was nothing new for the former ring headliner, but just the same, another embarrassing documentation of his well-published self-destruction. In early May of 1960, the longtime Minneapolis Star columnist, Cedric Adams, wrote of his run-in with Collins when he went to the county workhouse to report on conditions in the Minneapolis city jail. Collins was in the corridor and told Cedric, “I’m ashamed to have you see me like this.” It was Jimmy’s 105th time in jail on a drunk charge. He had been arrested on a Saturday and released the same day, only to be back in jail that same night.

Two years later, the man they once tagged “The Saint Paul Toy Bulldog” was dead at just 44 years-old. The heart that had never given up inside a prize ring, an alley, or a tavern, finally succumbed to years of booze. The story of Jimmy Collins is indeed a sad one of self-destruction, wasted talent, and pain. There’s the pain he caused inside the ring and inside bars to others, and then there is the self-inflicted pain he caused himself and ultimately cost him his life. Unfortunately, Minnesota has had plenty of boxers whose talent shined bright, but for this reason or that, never maximized that talent and found out just how far their fists could have brought them. Jimmy Collins was one those. Despite how he ended up, there was a time when the Irish kid with the warm smile, big right hand, and natural fistic ability, was something truly special. He remains one of the many fistic greats from the land of 10,000 lakes.